Difference between revisions of "Expanded or reference"

(Completed translation of the first two sections) |

(Further translation down to variable initisalisation) |

||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

<div id="ExpandedProperties"> |

<div id="ExpandedProperties"> |

||

| − | == |

+ | ==Principal characteristics of <tt>expanded</tt> type expressions== |

</div> |

</div> |

||

| − | + | An expanded type [[Glossary#Expression|expression]] has |

|

| + | properties which one needs to know. |

||

| − | propriétés qu'il est bon de connaître. |

||

| + | As explained above, the object that corresponds to an |

||

| − | Comme expliqué précédemment l'objet qui correspond à une |

||

| − | [[Glossary#Expression|expression]] |

+ | <tt>expanded</tt> type [[Glossary#Expression|expression]] cannot be referenced. |

| + | No other location can directly designate the object in question; in particular no pointer can point to it. |

||

| − | <tt>expanded</tt> ne peut pas être référencé. |

||

| + | So if, for example, one is dealing with a variable of type |

||

| − | Aucun autre endroit ne peut désigner directement l'objet en question, |

||

| + | [[library_class:INTEGER|<tt>INTEGER</tt>]], the only way of operating on the corresponding object is to use the variable in question. |

||

| − | en particulier par l'intermédiaire d'un pointeur. |

||

| − | Ainsi, si l'on dispose par exemple d'une variable de type |

||

| − | [[library_class:INTEGER|<tt>INTEGER</tt>]], la seule façon d'intervenir |

||

| − | sur l'objet correspondant implique de pouvoir utiliser la variable en |

||

| − | question. |

||

| − | + | An <tt>expanded</tt> type [[Glossary#Expression|expression]] always designates an object. |

|

| + | In other words, an <tt>expanded</tt> expression is never [[Void|<tt>Void</tt>]]. |

||

| − | toujours un objet. |

||

| + | What is more, an <tt>expanded</tt> type [[Glossary#Expression|expression]] always corresponds to one and only one category of object. |

||

| − | Autrement dit, une expression <tt>expanded</tt> n'est jamais [[Void|<tt>Void</tt>]]. |

||

| + | In consequence, [[Dynamic dispatch|dynamic dispatch]] is never involved when an <tt>expanded</tt> object is the target of a call (that is, on the left of a dot). |

||

| − | Qui plus est, une expression de type <tt>expanded</tt> correspond toujours |

||

| + | The invocation of a [[Glossary#Method|method]] with an <tt>expanded</tt> object as target corresponds to the most efficient possible direct call. |

||

| − | à une et une seule catégorie d'objet. |

||

| − | Par conséquent, il n'y a jamais de [[Dynamic dispatch|liaison dynamique]] en cas d'utilisation |

||

| − | d'un objet <tt>expanded</tt> comme cible d'un appel (i.e. à gauche du point). |

||

| − | L'invocation d'une [[Glossary#Method|méthode]] avec un objet <tt>expanded</tt> comme |

||

| − | cible correspond à un appel direct aussi efficace que possible. |

||

| + | Without going into too much detail, since dynamic dispatch is not possible with an <tt>expanded</tt> object, it is useless to give such an object the information that lets you find its [[Glossary#DynamicType|dynamic type]]. |

||

| − | Sans entrer trop dans les détails, comme la liaison dynamique n'est pas possible avec |

||

| + | Thus, the memory space required for an <tt>expanded</tt> object is limited exactly to that needed to accommodate its different [[Glossary#Attribute|attributes]]. |

||

| − | un objet <tt>expanded</tt>, il est inutile d'équiper un tel objet avec une |

||

| − | information permettant de retrouver le [[Glossary#DynamicType|type dynamique]]. |

||

| − | Ainsi, la place mémoire pour un objet <tt>expanded</tt> se limite très exactement à la place |

||

| − | mémoire pour ranger ses différents [[Glossary#Attribute|attributs]]. |

||

<div id="AutomaticInitialization"> |

<div id="AutomaticInitialization"> |

||

| − | ==Initialisation |

+ | ==Initialisation of variables and attributes== |

</div> |

</div> |

||

| − | + | In Eiffel, all variables are always initialised automatically. |

|

| − | + | This is the same for all kinds of variables: |

|

| − | [[Glossary#InstanceVariable| |

+ | [[Glossary#InstanceVariable|instance variables]], |

| − | [[Syntax diagrams#Routine|variables |

+ | [[Syntax diagrams#Routine|local variables]] and the |

| − | variable [[Syntax diagrams#Result|<tt>Result</tt>]] |

+ | variable [[Syntax diagrams#Result|<tt>Result</tt>]] which is used to hold the result of a function. |

| + | The way in which a variable is initialised depends entirely on its declaration type, which is either reference or <tt>expanded</tt>. |

||

| − | résultat d'une fonction. |

||

| − | La façon d'initialiser la variable dépend uniquement de son type de |

||

| − | déclaration qui est soit un type référence soit un type <tt>expanded</tt>. |

||

===Initialisation des variables de type référence=== |

===Initialisation des variables de type référence=== |

||

Revision as of 11:32, 6 November 2005

*** Translation in progress: Oliver Elphick 6/11/2005 *** *** first 2 sections completed ***

In our opinion, it is essential to have a good understanding of how objects are represented in memory while an application is running. The aim is not to make every one of us an expert in the subject, but more simply to have sufficient knowledge to be able to make design choices. Besides, it is often essential to be able to design(?) objects in memory so as to be able to explain or think about the design of a new class. The section which explains the two categories of objects which exist during execution is essential. Next, a summary of the properties of expanded types goes into detail about certain points that are characteristic of these types.

You have to realise that all variables are automatically initialised in accordance with their declared type. This too needs to be understood.

The last section is only of interest to those few users who wish to define their own expanded class. This section can be skipped by most beginners.

Expanded or reference objects, the choice

The objects that are handled during the execution of an Eiffel program are handled either with or without an intermediate reference. Furthermore, when an object is handled through a reference, it can be handled only through a reference. In the same way, when an object is handled without a reference, it can only be handled in that way, that is to say without any intermediate reference.

Thus there are two sorts of objects. The most common classes correspond to objects that are handled through a reference. Less often, classes correspond to objects that are handled without an intermediate pointer. In this case, the class in question begins with the keyword expanded. In Eiffel jargon, when we speak of an expanded class, we are talking about a class whose objects are handled without an intermediate pointer, objects that are directly written, or expanded, onto the memory area that they use. In contrast, if we talk of a reference class or of a reference type, it is to emphasise that the objects in question are not expanded.

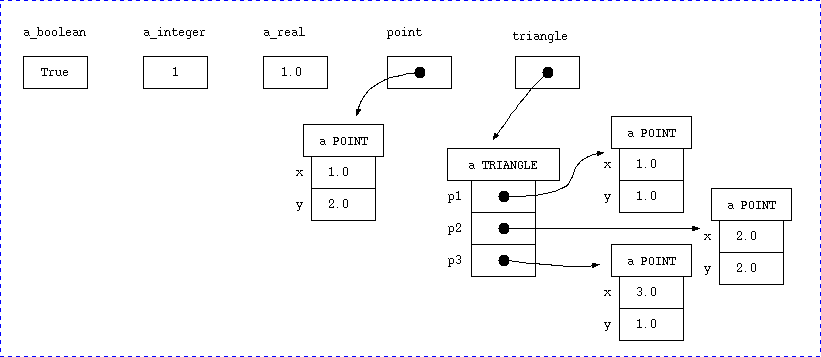

The chief point of this dichotomy is to make it possible to integrate the most basic entities into the object model. For example, a boolean value of the BOOLEAN class corresponds to an expanded object. Similarly, the classes INTEGER and REAL are also expanded. The following diagram shows what happens in memory; the classes POINT and TRIANGLE are ordinary classes, that is to say classes defined without the keyword expanded:

In the figure above, the variable called a_boolean is declared as type BOOLEAN. Since the BOOLEAN class is expanded, the corresponding object is directly assigned to the memory area associated with the variable a_boolean. As the diagram shows, the a_boolean variable actually contains an object True which corresponds to the boolean value true. In the same way, the memory area associated with the variable a_integer of type INTEGER directly contains the object corresponding to the value 1 since the INTEGER class is also expanded. Finally, the variable a_real declared in the example as type REAL also directly contains the value 1.0.

In the diagram above, the variable point is declared as type POINT. Since we are not dealing with an expanded class, the memory area associated with the variable point does not directly contain the POINT object, but a pointer to that object. Thus the point variable does not directly contain an object of the POINT class; the point variable references a POINT object. Note that the diagram also shows us that each object of class POINT is itself made up of two attributes x and y whose type is REAL. As in the case of the point variable, the variable triangle is a reference to an object of the class TRIANGLE since the TRIANGLE class is an ordinary class, not expanded. Since the attributes p1, p2 and p3 are of the POINT type, in this case there are also pointers to the corresponding objects.

Whether or not an object is expanded, the syntax used to declare it is the same. The fact that a class is expanded or not depends only on the class definition itself. For example, the declaration of the variables a_boolean, a_integer, a_real, point and triangle corresponds to the following Eiffel code:

a_boolean: BOOLEAN; a_integer: INTEGER; a_real: REAL; point: POINT; triangle: TRIANGLE

Whether or not one is dealing with an expanded object, the notation is just the same. For example, the following instruction copies into the variable a_real the value of the attribute y of the POINT object referenced by the variable point:

a_real := point.y

The following instruction copies the pointer which points to the same POINT as the one referenced by the p1 attribute of the TRIANGLE which is itself referenced by the variable triangle:

point := triangle.p1

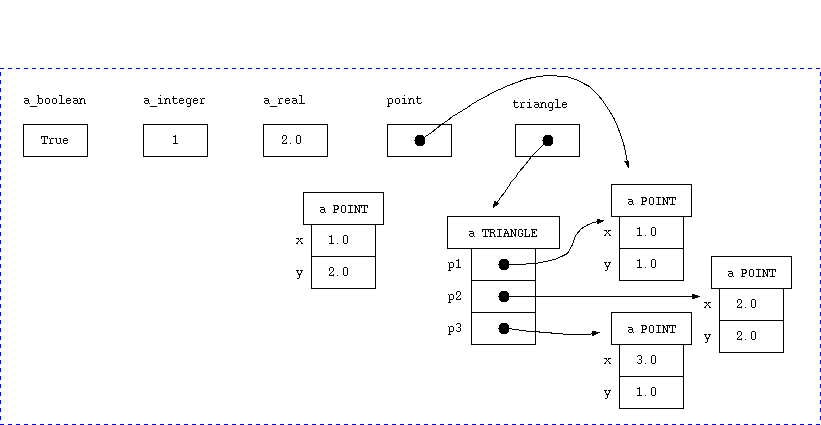

Without going into all the details of allocation, the effect of those two instructions in relation to the memory diagram above is to produce this memory configuration:

Applying a method to an expanded object uses the same syntax as for an ordinary (not expanded) object. For example the following instruction applies the sqrt function to the INTEGER class object which is stored directly in the memory area associated with the variable a_integer. The result of calling the sqrt function is a REAL which overwrites the old object which was formerly stored directly in the variable a_real:

a_real := a_integer.sqrt

Having identical notation for handling ordinary (referenced) and expanded (not referenced) objects simplifies programming and provides consistency.

Being able to describe basic objects by a proper class is an important aid to consistency. A simple object, such as a 32 bit signed integer, is described by a proper class, the INTEGER class. As with any class, it is possible to change or adapt the methods in the INTEGER class. Of course, nearly all users only consult the list of available methods. Since the INTEGER class is used by almost every program, altering it is more and more an uncommon event, and must be done with care. Nevertheless, having a proper class lets users look up the list of available methods for INTEGER in the same way as they can for all other classes.

Among the predefined expanded classes corresponding to basic objects that must be familiar to all users, let us list: BOOLEAN, INTEGER, REAL and CHARACTER. A well-informed user should also know the following expanded classes: INTEGER_8, INTEGER_16, INTEGER_32, INTEGER_64, REAL_32, REAL_64, REAL_80, REAL_128, REAL_EXTENDED and finally, for the most curious, the classes POINTER and NATIVE_ARRAY.

Principal characteristics of expanded type expressions

An expanded type expression has properties which one needs to know. As explained above, the object that corresponds to an expanded type expression cannot be referenced. No other location can directly designate the object in question; in particular no pointer can point to it. So if, for example, one is dealing with a variable of type INTEGER, the only way of operating on the corresponding object is to use the variable in question.

An expanded type expression always designates an object. In other words, an expanded expression is never Void. What is more, an expanded type expression always corresponds to one and only one category of object. In consequence, dynamic dispatch is never involved when an expanded object is the target of a call (that is, on the left of a dot). The invocation of a method with an expanded object as target corresponds to the most efficient possible direct call.

Without going into too much detail, since dynamic dispatch is not possible with an expanded object, it is useless to give such an object the information that lets you find its dynamic type. Thus, the memory space required for an expanded object is limited exactly to that needed to accommodate its different attributes.

Initialisation of variables and attributes

In Eiffel, all variables are always initialised automatically. This is the same for all kinds of variables: instance variables, local variables and the variable Result which is used to hold the result of a function. The way in which a variable is initialised depends entirely on its declaration type, which is either reference or expanded.

Initialisation des variables de type référence

Une variable dont le type est un type référence est toujours initialisée automatiquement avec Void. Par exemple, si on déclare une variable de type POINT ou de type TRIANGLE, les classes non expanded de l'exemple utilisé précédemment, la variable est automatiquement initialisée avec Void. Pour les types référence, il n'y a jamais de création automatique d'objet suite à la déclaration d'une variable.

Parmi les classes ordinaire usuelles, classes correspondant à un type référence, citons la classe STRING. Pas de cas particulier pour cette classe. Une variable déclarée de type STRING est automatiquement initialisée avec Void. Aucun objet de la classe STRING n'est crée lors de la déclaration d'une variable dont le type est STRING. Pour prendre un autre exemple courant, une variable déclarée avec le type ARRAY[INTEGER] ne provoque pas, lui non plus, la création automatique d'un tableau d'INTEGERs car la classe ARRAY elle même est bien une classe non expanded. Ainsi, cette règle d'initialisation simple s'applique à la majeure parties des classes qui, rappellons le, sont des classes ordinaire, des classes non expanded.

Initialisation des variables de type expanded

Les variables dont le type est expanded sont également initialisées automatiquement. Pour certains types expanded véritablement élémentaires, l'initialisation est prise en compte directement par le compilateur. Après avoir présenté tous ces cas particuliers, le cas général d'une classe expanded sera traité.

Pour la famille des INTEGERs, c'est à dire pour l'ensemble des types suivants, {INTEGER_8, INTEGER_16, INTEGER_32, INTEGER, INTEGER_64}, l'objet servant à initialiser correspond à la valeur 0.

Pour l'ensemble des types {REAL_32, REAL_64, REAL, REAL_80, REAL_128, REAL_EXTENDED}, l'objet servant à initialiser les variables correspond à la valeur 0.0.

Pour le type BOOLEAN, c'est la valeur False qui sert à initialiser.

Pour le type CHARACTER, c'est le caractère dont le code ascii est 0 qui sert à initialiser. Ce caractère se note '%U' en Eiffel.

Pour le type POINTER, l'initialisation des variables est faites avec la valeur machine permettant de représenter le pointeur null. Comme cette valeur n'est pas d'un usage courant, il n'existe pas de notation Eiffel pour dénoter cette valeur. Il faut utiliser la méthode is_null de la classe POINTER pour tester le fait qu'une expression de ce type correspond à la valeur null.

Dans le cas général, c'est à dire pour une classe expanded ne faisant pas partie des cas particuliers précédents, l'initialisation est programmé par le concepteur de la classe. En fait, une classe expanded doit avoir un et un seul constructeur sans argument. C'est cette procédure de création qui est déclenchée automatiquement pour réaliser l'initialisation.

Quelques conseils avant d'écrire une classe expanded

En général, il n'est pas utile de définir de nouvelles classes expanded et ceci pour la très grande majorité des applications. Comme nous l'avons présenté dans ce qui précède, l'intérêt principal des classes expanded est de pouvoir intégrer les objets les plus élémentaires dans le modèle objet. Ceci étant dit, il peut être utile de recourir à une classe expanded soit pour mettre à disposition un ensemble de routines utilitaires, soit pour économiser de la mémoire dans le cas particulier de l'utilisation d'un très grand nombre d'objets de petites tailles. Enfin, pour finir, nous présenterons les pièges à eviter lors de la conception d'une classe expanded.

Regroupement d'un ensemble de routines

Avec un langage à objets, il convient toujours, quand cela est possible, de placer les méthodes de manipulation des objets directement dans la classe des objets que l'on manipule. Dans certains cas bien particulier, il n'est pas souhaitable ni même possible de respecter cette règle de base. La classe COLLECTION_SORTER est un bon exemple d'utilisation d'une classe expanded afin de regrouper des routines qui ne peuvent pas être rangées directement dans les classes correspondant à la notion de COLLECTION.

En effet, bien que toutes les routines de la classe COLLECTION_SORTER servent en fait à trier des objets de la famille des COLLECTIONs, il n'est pas possible de mettre ces méthodes directement dans la classe COLLECTION. Ceci n'est pas possible pour la raison simple que toutes les COLLECTIONs ne peuvent pas être triées. Seules les COLLECTIONs dont les élements sont COMPARABLE peuvent êtres triées. Ainsi, la classe COLLECTION_SORTER permet d'ajouter cette contrainte générique supplémentaire. La classe COLLECTION_SORTER ne comporte aucun attribut; ce n'est en fait qu'un réservoir à méthodes. En outre, cette classe est expanded. Ainsi, pour trier par exemple un tableau d'entier on peut procéder de la manière suivante :

local sorter: COLLECTION_SORTER[INTEGER] array: ARRAY[INTEGER] do array := <<1,3,2>> sorter.sort(array)

L'intérêt d'avoir utilisé dans ce cas une classe expanded réside dans le

fait qu'il n'est pas nécessaire d'allouer dans le tas un objet

de la classe

COLLECTION_SORTER[INTEGER].

Vous l'avez bien sûr remarqué en lisant le code qui précède, il n'y a aucune instruction

de création pour l'objet associé à la variable sorter.

En outre, comme les objets de cette classe n'ont aucun attribut, l'objet correspondant

à sorter n'est même pas représenté dans la pile !

L'utilisation d'un objet expanded permet ici d'obtenir les meilleurs

performances.

Économie de mémoire pour de petits objets très nombreux

Une autre utilité des classes expanded consiste à pouvoir économiser de la place mémoire pour les objets de petite taille. Nous entendons ici par objet de petite taille un objet dont la taille mémoire est comparable ou légèrement supérieure à la taille d'un pointeur en machine. En effet, si l'on considère pour simplifier, qu'un objet de la classe FOO fait exactement la taille d'un pointeur machine et que l'application utilise n objets de la classe FOO, il faut alors au minimum 2 * n emplacements mémoire de la taille d'un pointeur machine. Si on change la définition de la classe FOO et que l'on définit cette classe comme étant expanded, on économise alors n emplacements mémoire de la taille d'un pointeur de la machine.

Attention, car pour pouvoir profiter de ce gain, il faut également être dans un cas très particulier dans lequel la liaison dynamique n'est pas utile avec une variable de type FOO. En effet, comme indiqué précédemment, dès qu'une expression est expanded on ne peut plus profiter de la liaison dynamique.

Comme dans le cas précédent, l'utilisation d'une classe expanded à la place d'une classe ordinaire permet une économie de mémoire. Notons également que les objets en question ne peuvent plus être identifiés par leur addresse mémoire. En effet, quand le type FOO est expanded, la comparaison de deux variables de ce type avec l'opérateur = ne compare plus deux addresses, mais bien deux objets. Il faut également être conscient de ce dernier point avant d'opter pour la définition d'une classe expanded.

Les pièges à éviter avec les classes expanded

Le premier piège à éviter concerne les classes ayant de nombreux attributs. Quand un objet expanded est très gros, le passage en paramêtre de cet objet en tant qu'argument d'une routine peut se révéler beaucoup plus coûteux qu'avec un objet ordinaire. En effet, pour un objet ordinaire, c'est uniquement l'adresse mémoire de cet objet qui est recopiée dans la pile. Pour un objet expanded, c'est l'objet lui même, c'est à dire tous ses attributs qui sont recopiés lors du passage en paramêtre. Notons que le même effet peut se produire dans le cas de l'affectation d'une variable dont le type est expanded. Pour les très gros objet expanded, l'affectation peut se révéler moins performante.

Le deuxième piège à éviter est beaucoup plus pervers car il ne risque pas seulement de ralentir l'exécution de l'application. Ce piège concerne l'interprétation trompeuse que l'on peut donner a un appel de procédure de modification appliquée sur un objet expanded obtenu par le biais d'une lecture indirecte d'attribut :

bar.foo.set_attribute(zoo)

équivaut en fait à la séquence de deux instructions suivante :

temporary_foo := bar.foo -- (1) recopie de l'objet expanded foo temporary_foo.set_attribute(zoo) -- (2) application de la modification sur la copie de foo

En effet, même si foo est un attribut, la classe de foo étant expanded, une recopie de l'objet correspondant est effectuée. L'objet que l'on pensait modifier à l'aide de la procédure set_attribute n'est donc pas celui qui est associé à l'attribut foo, mais une copie mémorisée dans une variable temporaire ! Notons que lorsque foo est un appel de fonction, la transformation précédente qui introduit la variable temporary_foo ne change rien. Il en est de même, si foo est un type référence.

Malheureusement, le compilateur actuel ne signale pas encore ce piège. Nous avons prévu, mais ceci n'est pas encore implanté, de modifier le compilateur afin qu'il puisse prévenir de l'éventualité de ce piège sous la forme d'un message d'avertissement. À l'heure actuelle (aout 2005), rien n'est encore décidé / implanté, mais il est probable que, dans le futur, le compilateur vous demande d'ajouter explicitement la variable temporaire afin que l'on soit conscient de l'éventuel problème. Comme plusieurs solutions sont envisageables, y compris l'ajout de nouvelles restriction concernant la définition des classes expanded il convient en attendant d'être prudent lors de la définition de nouvelles classes expanded.

Pour éviter de tomber dans ce piège délicat, il est préférable quand cela est possible d'éviter d'exporter les méthodes de modification des classes expanded. Le mieux est encore de ne pas avoir de procédure de modification du tout. Notons que toutes les classes élémentaires expanded suivantes respectent cette régle. Il n'y a pas de procédure de modifications dans les classes : BOOLEAN CHARACTER, INTEGER_8, INTEGER_16, INTEGER_32, INTEGER, INTEGER_64, REAL_32, REAL_64, REAL, REAL_80, REAL_128, REAL_EXTENDED et POINTER. Tant que le compilateur ne sera pas capable de vous avertir de cet éventuel problème, soyez prudent quand vous utilisez des classes expanded.